Just before Christmas, the Government issued its decision on future guidance and support for electricity interconnectors: high-voltage cables that connect the electricity systems of neighbouring countries.

The government regulator for electricity and gas markets in the United Kingdom, known as Ofgem, stated in this guidance that the government would be inviting bids to bring forward billions of pounds of investment in new electricity interconnectors to help boost energy security, hit the country’s climate goals and save money for energy consumers.

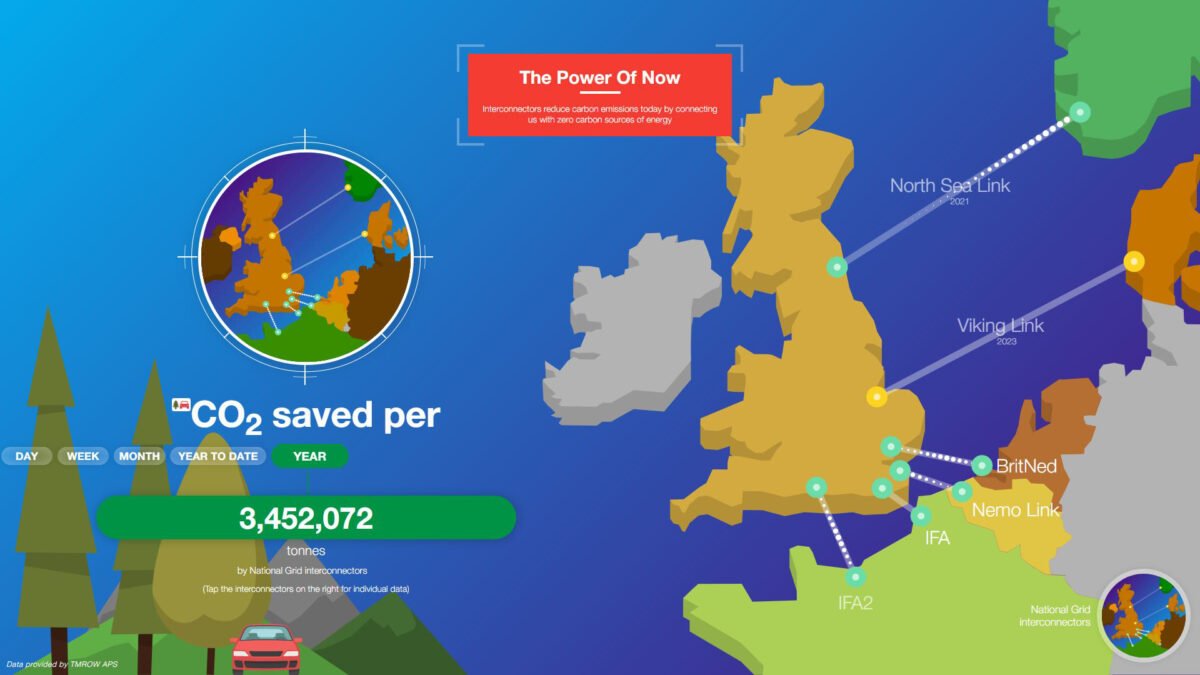

Electrical interconnectors allow countries to share electricity and can switch quickly between importing and exporting power. Currently, Britain has seven operational electricity interconnectors, connecting it to Ireland, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Norway. These provided almost 7% of the UK’s electricity last year. However, the UK Government wants to more than double existing interconnector capacity by 2030 to support its target of quadrupling offshore wind capacity by the same year.

The UK’s oldest interconnector is with France and the Interconnexion France-Angleterre (IFA1) was commissioned by the Central Electricity Generating Board in 1986.

Fast forward to the end of 2021 and the UK has IFA2 in operation along with connections to the Netherlands, Belgium, Norway and the Irish Republic with links to Denmark and other countries under construction, consented or in preparation.

A great benefit of interconnectors is how they support renewable energy. Renewables are often called ‘intermittent generation’ due to fluctuations in weather conditions: lots of wind farm power when it gusts and plenty of hydropower after heavy rainfall. Energy demand in different countries and time zones varies. There can be periods where more renewable energy is generated than the domestic demand requires. Therefore, having a way to allow surplus wind, hydro or solar power in one system to be offloaded to other markets, supports investment and ensures that there are opportunities for returns.

Consider a storm coming across the Atlantic to Ireland, sweeping east across the UK and into continental Europe, with its rainfall leading to over-topping of the Nordic dams and spillways. If the turbines spin in Ireland but demand is low, a great deal of energy is captured and lost. Although storage technology is developing, meeting demand is the most efficient way to exploit the resource. Interconnectors allow this to happen very efficiently, maximising the use of the natural resource by exporting to Northern Ireland and Wales.

As the wind moves across the UK and toward the North Sea, we can export surplus power back to Ireland as it experiences the calm after the storm, as well as east to our neighbours across the Channel. As our wind drops, the direction of power flow may change so we import electrical power as others’ turbines spin, allowing us to use that in preference to fossil fuel generation.

The benefits to the diversity of supply, security of connections and the support of renewable energy are reasons why interconnectors receive such favour from governments.

As an island state, the mainland UK’s connections are by subsea cables and use direct current (DC) whereas our onshore network uses alternating current (AC). Large buildings are needed to house the converter stations where AC is changed to DC and vice-versa. Finding appropriate converter station sites, cables routes and connections to the existing power grid and then gaining consent for these infrastructure components are time-consuming and challenging activities.

TEP has provided environmental planning expertise in relation to many of the operational interconnectors and those under development in the UK; we have a track record in helping deliver these projects stretching over almost a quarter of a century. We are proud of our involvement in these projects and the contribution they make in enabling the nation’s businesses and homes to edge nearer to net-zero.