The Heritage team at TEP recently produced an archaeological desk-based assessment (DBA) for a proposed development in Liverpool. For the DBA, a site visit was undertaken by Historic Environment Consultant Brandon Braun. While assessing the potential impacts on designated heritage assets, Brandon came across the Huskisson Monument in the cemetery near the Anglican Cathedral. Based on its architectural features, the Huskisson Monument strongly reminded him of his PhD research and inspired him to write the following article.

The Huskisson Monument was erected in 1836 as a commemorative monument of the MP for Liverpool William Huskisson, who was tragically killed in 1830 following an accident at the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. The monument originally housed a statue of Huskisson by John Gibson, although this has now been removed. Today, it stands alone in the shadow of the Anglican Cathedral in Liverpool, several meters below ground level in a former quarry that was converted into a cemetery in the 20th century.

The Huskisson Monument is circular in plan, comprising a rotunda of Corinthian columns atop a round stone pedestal. Between the Corinthian columns are stone block masonry walls, pierced by high square windows covered by metal grills. The columns support a Corinthian entablature with an undecorated freeze, above which sits a domed roof sheeted in bronze and capped with a cross.

If the image of the monument or any part of its description seems familiar to you, it is for good reason. The Huskisson Monument is based on the well-known Choragic Monument of Lysikrates from Athens, Greece dating to the fourth century BCE–more than 2 millennia earlier!

There are several reasons why the solemn stone monument in Liverpool is so similar to its Ancient Athenian counterpart. The Huskisson Monument was designed by John Foster, an architect and supporter of the Greek Revival Style. The Greek Revival was rooted in the custom of the Grand Tour of the 17th to 19th centuries, in which wealthy/aristocratic young men, primarily from Britain and western Europe, would spend months (or years!) travelling through Europe as part of their coming-of-age. Lands of Classical Antiquity, that is primarily Italy, Greece, Turkey and the eastern Mediterranean, were prominent legs of the itinerary on these trips, and left lasting impressions: think Lord Byron in this picture:

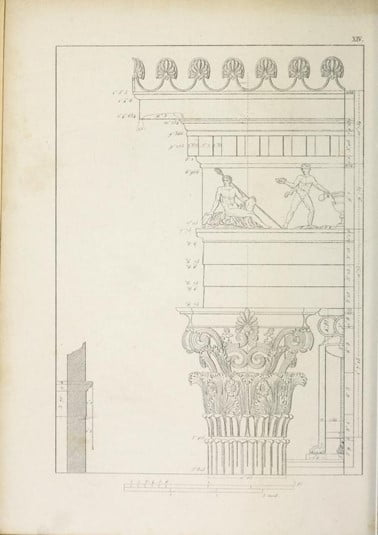

Interest in the monuments, artefacts and ruins of the Mediterranean during the Grand Tour led to research into the prominent physical remains of the past, such as standing architecture. A prominent example of this is the work of James Stuart and Nicolas Revett, The Antiquities of Athens, published in 1762 and based on fieldwork from earlier in the century. Stuart and Revett produced measured drawings of extant architectural features, while also reconstructing what they would have looked like in antiquity. You might recognise this engraving (or others like it), which adorns many a wall today, as well as the particular capital that it reproduces:

Not only was John Foster in the post-Stuart and Revett generation and a participant in the Grand Tour himself, but he also took part in expeditions to record the architecture of ancient monuments, such as the Temple of Apollo at Bassai from the fifth century BCE. This is notable because the temple at Bassai is one of the earliest examples of the Corinthian capital, one of the key architectural elements that is prominent in both the Lysikrates Monument and the Huskisson Monument.

All that being said, there are many differences between the Huskisson Monument and the Lysikrates Monument, from particular parts of their architecture and decoration, to their placements and prominence, all of which can be explained partly by their difference in function.

The Lysikrates Monument is at a well-known topographical spot in Athens, in a prominent spot beneath the Akropolis and up the road from Hadrian’s Gate. In antiquity, it would have stood among other similar monuments, conspicuously lining a road among a series of similar monuments.

And that conspicuousness was its exact purpose. The Lysikrates Monument was designed as a prominent display celebrating the victory of Lysikrates in a musical contest in 335 BCE. Everything about it is showy, from its location, artificial elevation by a tall plinth (whose square plan and different stone juxtaposed and emphasised the monument), shining marble construction material, ornate architectural design and detailed sculptural program that sang victory.

In contrast, the Huskisson Monument commemorated the MP William Huskisson and served as a mausoleum. The interior space of the monument, accessed through a door on the western side of the round pedestal, was filled by an over-life-size statue of Huskisson standing atop an inscribed stone plinth. The high windows allowed light into the monument, focusing on the stone representation of the deceased MP. The absence of external sculptural decoration reinforces the primacy and solemnity of the interior space.

The placement of the Huskisson Monument, whether standing alone in the centre of the cemetery as today or surrounded by lower-standing headstones and monuments as it had earlier in the 20th century, supplements the solemnity of the mausoleum, as does its location several meters below surface level and in the shadow of the looming Anglican Cathedral (after the early 20th century).

This brief analysis is only part of the interesting interconnections between the Huskisson Monument in Liverpool and the Lysikrates Monument in Athens, and there are many further avenues that can be explored, such as:

-by Brandon Braun, Historic Environment Consultant, TEP

If the reader is interested, Brandon would be happy to discuss these monuments or provide a bibliography! Feel free to get in touch using brandonbraun@tep.uk.com.