Human beings are obsessed with water. It makes up over 60% of our bodies, we drink it, bathe in it, swim in it and spend our leisure time by the sea and beach just to be near it. Our connection with water has been studied by scientists who note that an instant positive response is generated in our brains when we are near water, releasing neurochemicals that improve blood flow to the brain and heart, making us feel more relaxed and increasing our sense of wellbeing. This appreciation of the importance that water plays in our lives has long been understood by our ancestors and has been demonstrated in the British archaeological record going back to prehistoric times.

Archaeologists have discovered numerous human occupation sites near rivers, streams and springs and archaeological evidence appears to demonstrate that this was not just for practical purposes, such as strategic locations for hunting and fishing, but also for other less tangible reasons. Discoveries of votive deposits in watercourses appear to show that people were deliberately placing items of importance in the water, such as metalwork, including gold objects and decorative weapons, as well as both human and animal remains. Settlements near rivers have also included ‘shrine’ buildings often dating from the Iron Age and Roman periods and such structures are interpreted to be related to a belief in water gods and spirits.

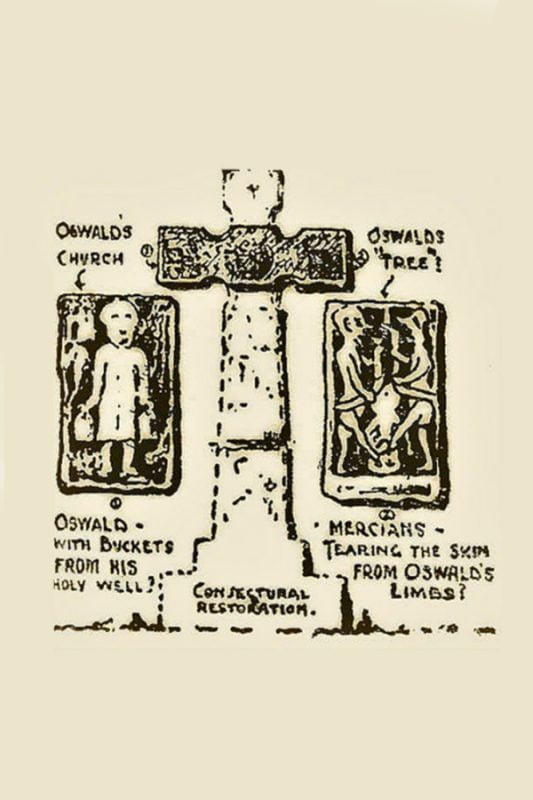

The belief in water spirits continues to endure into the modern-day through rural traditions such as the custom of well-dressing with flowers, undertaken in places such as Derbyshire and Staffordshire. This practice is thought to derive from early pagans giving floral offerings to water spirits. Many of the wells which were the focus of religious or ritual activity during pre-Christian times were subsequently rededicated in honour of Christian saints and later, chapels were often built over these sacred places. Traditions also attribute the location of holy wells to have sprung up in places where early saints were killed or buried. The heritage team at TEP has worked on several heritage assessments where these sacred places are designated as heritage assets and recorded in the local Historic Environment Record, and in some instances are Scheduled Monuments, protected by Historic England. Two recent examples that TEP has come across during project work are holy wells dedicated to St Alban and St. Oswald, both of which have fascinating traditions and legends associated with the origins of the sacred water well or spring.

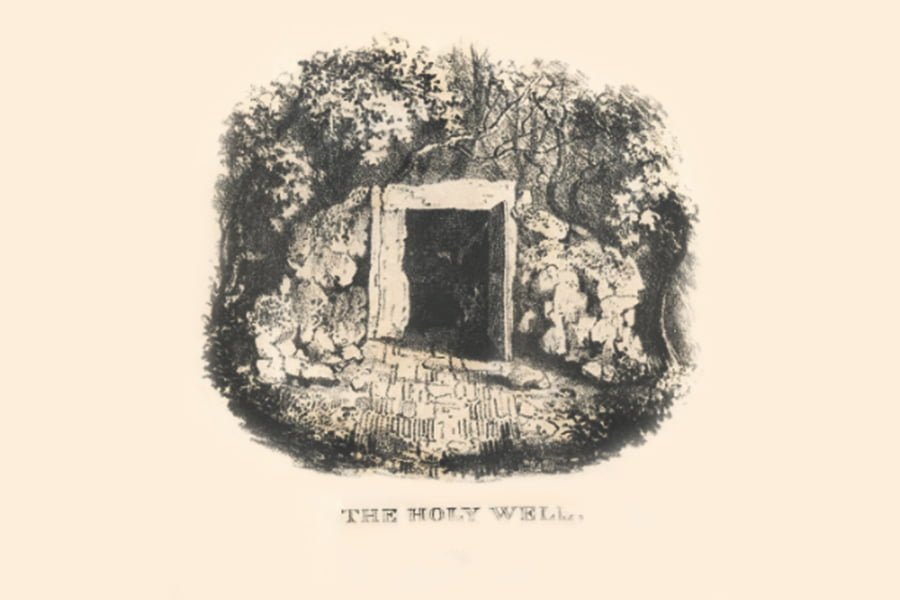

There are at least five holy wells dedicated to St. Oswald, one of which is located in Cheshire near the village of Winwick. One of the many stories associated with the saint tells us that Oswald, who was King of Northumbria in the 7th century AD, came to visit Winwick before his death in battle against King Penda of Mercia. The battle is recorded in the 8th-century writings of the Venerable Bede, however the site of this battle is not confirmed and different historical accounts put its location in a number of places, including Cheshire, and also Oswestry in Shropshire, where there is another holy well dedicated to Oswald. The remains of St Oswald after his martyrdom and associated relics were frequently moved around the country, which may account for the number of wells in his name. A much later 16th-century story tells of the belief at that time that the well in Oswestry was created when “An eagle snatched away an arm of Oswald from the stake, but let it fall in that place where now the spring is”.

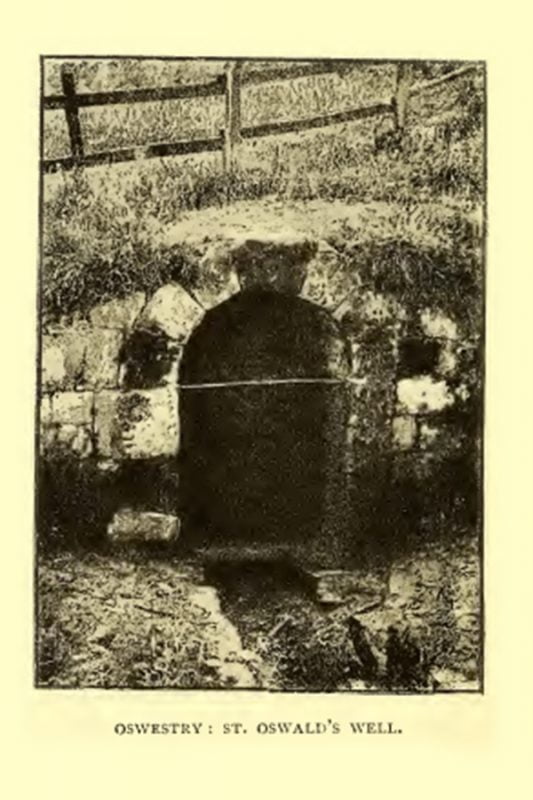

In Winwick, St Oswald’s Church is suggested to have been built on the site of a pre-11th century chapel, and before that a pre-Christian, pagan temple. In 1873 part of an Anglo-Saxon (7th – 9th century) stone cross was discovered in the churchyard, and its carvings were interpreted as showing St Oswald at the time of his martyrdom, being hung upside down by two soldiers. Another unusual carving in the tower of St Oswald’s Church is that of ‘The Obstinate Pig’. The local story goes that a new church was being built in Winwick to commemorate St Oswald in another location. However, one night a pig was seen running to the place of the present church and crying “We-ee-wick” and this was taken as an omen or sign to move the church to the spot chosen by the pig. It is also said that the animal picked up the foundation stone in its mouth and brought it to the place where St Oswald’s Church now stands, and the pig’s cry of “We-ee-wick” is where the village got its name.

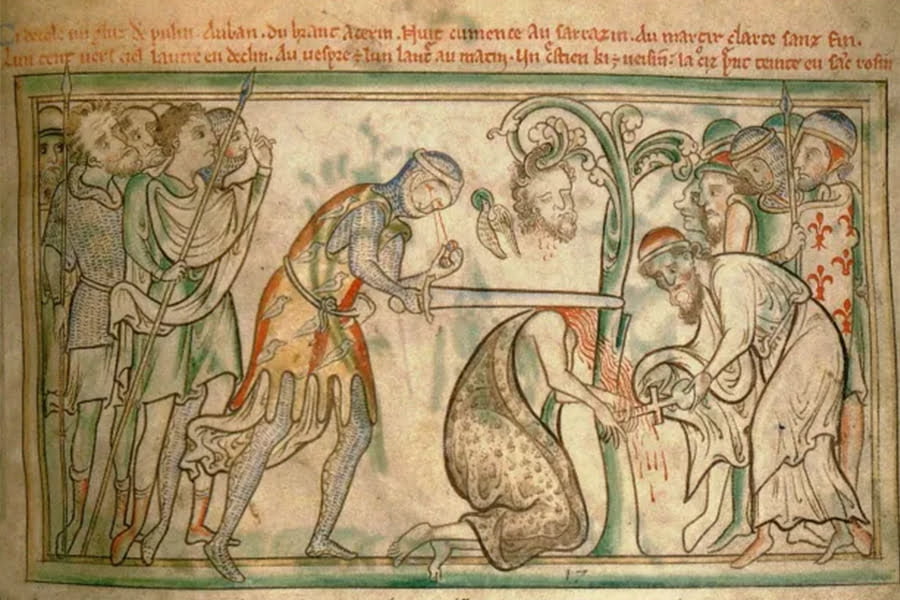

The Venerable Bede also recorded in his writings the life and martyrdom of St Alban, from which the city takes its name. Bede’s writings, four centuries after the time of St Alban, demonstrates that legends about the site of a holy well or spring created by St Alban were already established in tradition by that time. The tale records that Alban, a non-Christian resident of the Roman town of Verulamium in the 3rd or 4th century met and sheltered a Christian priest and subsequently converted to Christianity himself. His actions angered the Roman governor who condemned Alban to death. The legend as told by Bede says that on the way to his place of execution, a bridge across the River Ver was so full of spectators, the execution party could not cross, so Alban parted the waters so they could pass. Witnessing this miracle, the designated executioner immediately converted to Christianity ‘on the spot’ and refused to kill Alban. There was some delay in finding a replacement and during this time Alban and the party walked up to a neighbouring hill, now known as Holywell Hill, where he prayed for water to quench his thirst, and a fountain of water sprang up under his feet. He was then beheaded, along with the original executioner, and the head of St Albans rolled down the hill and where it rested a spring appeared, and it was here that the abbey dedicated to him was built. Bede also shares a rather gruesome detail of the story, later depicted on a medieval drawing, which was that as soon as the replacement executioner carried out his duty, his eyes supposedly dropped out of his head, in an act of Divine vengeance.

It is thought that there may be over 600 sites of holy wells in Britain and these heritage assets may not appear much more than a natural spring or a lined well shaft in the ground. However, they hold important historic, evidential and communal heritage values. The two examples included in this article only briefly cover the rich and fascinating history of our past relationship with and understanding of water and its importance to us within sacred places. Historic England has on its website some useful introductory guidance notes covering late prehistoric to post-roman shrines and ritual structures, and the book ‘The legendary lore of holy wells in England by Robert Charles Hope in 1893 can also be found online to explore this subject further. I will now wrap up this article with a final thought and an apt quote from the 19th-century teacher, poet and author Lucy Larcom, that “A drop of water, if it could write out its own history, would explain the universe to us”.

Sarah Hannon-Bland

Senior Historic Environment Consultant

(and member of the Society for Church Archaeology)

To read more from our Heritage team click here or to learn about our other Culture and Heritage projects click here.