Combatting climate change is going to come down to individuals taking responsibility for their own actions, led by government policy and incentives, as well as personal motivations. As members of the human race we are all responsible for making choices: how we live, travel, shop and consume, but what additional choices and decisions should the landscape professional be making? Here are some thoughts on ways that we can help tackle climate change and build resilience into landscapes, some borne out of my own experiences working at The Environment Partnership.

The planning and design of high-quality green space and the wider urban environment is of great importance in terms of sustainable place-making; supported by measures that reduce the need and desire to travel, we can combat one of the major causes of climate change. Encouraging travel by foot or by bicycle is a key role of the landscape professional.

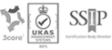

This is where joined-up and forward thinking comes into play through Green Infrastructure (GI) planning and strategy. GI strategies are vital for Local Planning Authorities to identify the bigger picture and to create opportunities for multi-functional green space corridors.

These corridors provide a means for attractive and pleasant off-road movement routes, which can have a functional role through the working-week, serving recreational needs at the weekends and during holidays.

This may seem an obvious one, but there are multiple benefits to tree planting in the context of climate change. Due to their size, trees are the best means of building carbon uptake and storage into new planting schemes. With changes to our climate resulting in extremes of weather, trees also offer important shade and shelter within the landscape for people and wildlife, and intercept rainfall and slow its progression downstream, helping to reduce peak flows and flood events. In an urban environment, where space may be constrained and land is at a premium, street trees bring all these benefits, as well as helping to counter the urban heat island effect during summer months.

Beyond trees, maximising opportunities for other types of planting is also a must. A multi-layered approach to planting that mimics natural habitats will bring optimum benefits. A shrub understorey and ground flora layer can also contribute to carbon capture, increase interception, reduce run-off and reduce the urban heat island effect, whilst also preserving well-structured soils fed with organic matter. The importance of good, healthy soils should not be underestimated in terms of the carbon sink that they provide and their resilience to extremes of weather. Good soil structure will aid drainage during periods of high rainfall, and organic content is essential for humus-rich soils to retain moisture for plants to use during periods of drought. For managed landscapes, the retention and application of shredded plant matter such as mulch, not only benefits the soil as it breaks down but also suppresses weeds, eliminating the need for hand weeding or herbicide application.

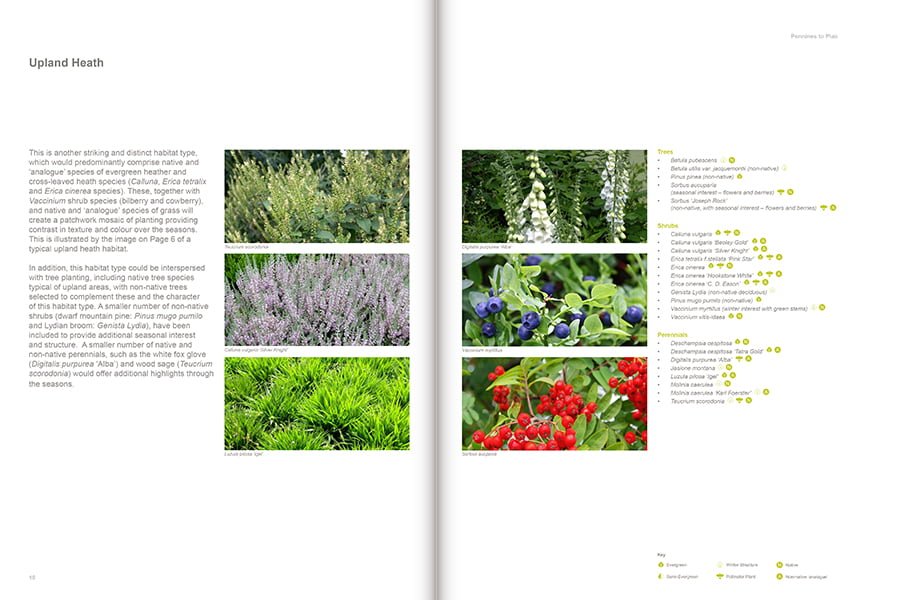

Having acknowledged the importance of planting, we should not overlook the specifics of what and where to plant. We know that native plant species support the widest range of faunal species, and support natural habitat systems and processes that keep the natural environment in check. Going forward, climate change presents an unknown, in terms of how our native species will adapt. Adaptation is the natural, correct and only response in this situation. To give our natural environment the best chance of doing this, as a general rule, we need to make new native planting as diverse as possible, providing the means for nature to find its own way through, whether certain species survive, thrive, or not. We know that across the UK there are variants within our native species, where local conditions have resulted in adaptation over time. Provided that climate change does not accelerate too quickly, the hope will be that the same will happen. The Forestry Commission’s current guidance on this topic (See the research publication) suggests that we should look to source two-thirds of new planting using seed which has originated from 2 degrees latitude further south to assist with this process, with the remaining stock comprising plants grown from local seed. Further to this, recent advice suggests that small amounts of provenance material from up to 5 degrees of latitude south of a site may be mixed into woodlands.

There is also the notion that certain UK native species will be better at coping with extremes of weather. For example, river floodplain plant species are used for periodic waterlogging, and dry periods during the summer months.

In terms of non-native planting, those that help support native faunal species, such as ‘pollinator plants’ should be promoted, as these will help bolster and promote these creatures.

For non-native planting, there is also a wider palette to select from in a process known as ‘climate matching’, with the opportunity to identify plants from around the world that will be suited to our future climate.

Climate change means that we are seeing prolonged periods of wet weather and an increase in flood events. The continued employment of Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS), which aim to slow surface water drainage flows and build water storage attenuation into projects, will help to minimise flood risks. However, there needs to be an acceptance that valley floodplains will be periodically inundated and the design and management of green spaces within these environments need to adapt to this. Working with drainage and flood engineers on creative solutions is vital, seeking opportunities for river restoration, the creation of areas that can provide flood storage capacity, and how this relates to the other uses and functions of the space. For example, raising main path routes up on embankments, which can also be used for the control of floodwaters, means that landscapes can still be accessed during flood events. Elsewhere, the design needs to be sufficiently robust to ensure that surfacing, boundary treatments and other elements can withstand floodwaters so that these do not have to be regularly replaced or repaired.

For the landscape professional the specification of hard landscape materials, in particular, whilst working to minimise climate change is a challenge. Natural hard landscape materials have the benefit of robustness and longevity, but the convenience of cheaper imports from overseas is hard to ignore. However ethically these may have been sourced, they may have travelled half-way around the world before reaching our ports. Man-made products may also be coming from overseas and whilst many now contain recycled components, what does their embodied carbon cost?

These are difficult decisions to make when budgets for delivery are tight. However, I would encourage an approach that makes the most of the materials and resources that may be on-site, looking to local suppliers whenever possible, and working to the simple premise of achieving a cut and fill balance within a site. This could be seen as a constraint, but in the same way that our ancestors, constrained by their local environment, designed and built character-filled and place-specific settlements, maybe this is an opportunity to achieve a greater level of creativity and avoid ubiquitous design?

Finally, the power of the community at a local level cannot be underestimated. Look at the impact of the incredible edible movement, borne out of the minds of two Todmorden residents, and now a national movement being adopted by towns and villages across the UK. The principle of local food growing and production is supportive of the local live, work and play agenda, reducing food miles and encouraging increased consumption of plant-based foods. There are plenty of other examples of community initiatives that are helping to tackle climate change, such as the Torrs Valley Hydro-electric project at New Mills, High Peak. As Landscape Professionals we regularly encounter ambitious community groups with great ideas. We have an opportunity to help them realise these plans, whether that is local food growing, renewable energy or other environmental schemes.

In conclusion, there is lots for us to do! I hope that this article brings the importance of the role of the landscape professional into focus. The climate change emergency is not going anywhere and it is the closest some of us may ever come to having a ‘key worker’ role. If collectively we pull together in the same direction, working in partnership with our clients, agencies and communities, we will minimise further change whilst delivering a well-considered, high quality and resilient landscape framework for the future.

Author

Charlotte Hayden

Associate Landscape Architect