Amir Bassir, Principal Historic Environment Consultant at TEP contributed an article for publication in the latest Volume of Church Archaeology Journal (Volume 22).

Amir writes:

I have had a long-standing interest in historic graffiti which provides a much more immediate connection to the past than other types of historic features. They can also be found in some unlikely places and it is fun to look out for them when out and about.

My article, “The challenges of recording, classifying, and interpreting historic church graffiti as heritage assets: a field archaeologist’s view”, examines the results of an archaeological survey of historic graffiti undertaken in 2016 on the roof of Beauchamp Chapel at the Church of St Mary, Warwick, and reviews the recording methodology employed at that site. The article also compares the results of that work in the context of data derived from other similar graffiti recording projects to assess the range of recorded graffiti types, their prevalence and date range, possible interpretations and thematic significance.

Historic graffiti can often be overlooked as heritage assets with their own inherent value and they very rarely even appear in Listing descriptions or general literature about historic buildings. However, these often-ephemeral features are surprisingly common and are a fascinating record of historic behaviour and values and can be unexpectedly encountered in some very unlikely places.

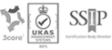

At Beauchamp Chapel for instance, the need to replace the roof leadwork resulted in a full record being made of the graffiti assemblage which would be lost. The 42 panels yielded a substantial assemblage of over 700 individual graffiti of which over half consisted of outlines of shoes. These were rendered in a range of styles and levels of detail and dated examples ranged from the 17th through to the 19th century. These types of graffiti can be found across the UK and the article highlights examples of churches from Warwickshire, Wiltshire and Yorkshire, including at Filey where an assemblage of 1500 graffiti included at least 47 renderings of ships and boats. Confusingly, shoe graffiti of an almost identical form has also been found on the stone parapet of a medieval bridge in Northamptonshire and as such, interpreting these features and the motivations of the people who made the graffiti is a difficult task. Other types of graffiti which can be found in churches and other places such as houses, include crosses, names and initials, outlines of hands, and a broad array of pictures including faces, horses, items of clothing, rifles, animals, and compass-drawn patterns.

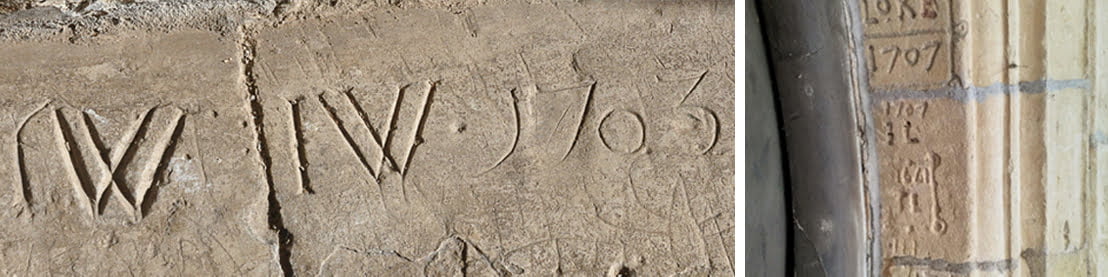

An example of modern graffiti encountered during a TEP project was a large assemblage of names and initials written on the walls of the stable clocktower at the National Trust property Tredegar House, Newport, which had been used as a POW camp during the Second World War. Alongside a large number of 18th and 19th century names and initials, the walls of the clock tower included numerous names of US service personnel, often with their rank and city or state of origin, as well as names of German origin, and frequently even the names of ships.

Thanks to popular publications, academic interest, and volunteer led projects, there are now greater efforts to preserve and record historic graffiti and it is hoped that an increased awareness among the general public and heritage managers will help prevent their accidental damage or destruction, as well as providing a greater appreciation of the historic environment.

by Amir Bassir, Principal Historic Environment Consultant, TEP

To read Amir’s article in full, please visit https://www.churcharchaeology.org/journal.

Back issues of the Church Archaeology Journal can be found at Library (archaeologydataservice.ac.uk)